The beauty of a broken window

Every year, we complete important repairs to many of our churches. These are not the biggest or most high-profile projects that we do, but we’re very proud of them. Good conservation is what keeps these wonderful buildings open and preserves their stories for everyone.

So we’re excited to announce that we recently entered two of our conservation projects into a prestigious competition. The Sir John Betjeman Award celebrates the best conservation work carried out on historic religious buildings in England and Wales, and is run by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Whether we win or not, we want to share these success stories to inspire heritage lovers across the UK. Here’s the first, about a particularly beautiful window at St Kenelm’s in Sapperton. You can read about the other project to repair damage done by vandals at All Saints' Church in Leigh here.

A window onto history

The history of St Kenelm’s stretches back to the 12th century, but the building has changed substantially over the years. In the early 18th century the nave and south transept were remodelled, and new round-arched windows were added. These windows used rectangular pieces of glass, known as ‘quarries’, held together with lead. The glass has a strong green tint as a result of the iron in the sand used to make it. It was much admired by members of the Arts and Crafts movement, including Ernest Gimson and the brothers Ernest and Sidney Barnsley, who settled in Sapperton village. During the 20th century all but one of the windows were restored: new leading was added and much of the original glass was replaced.

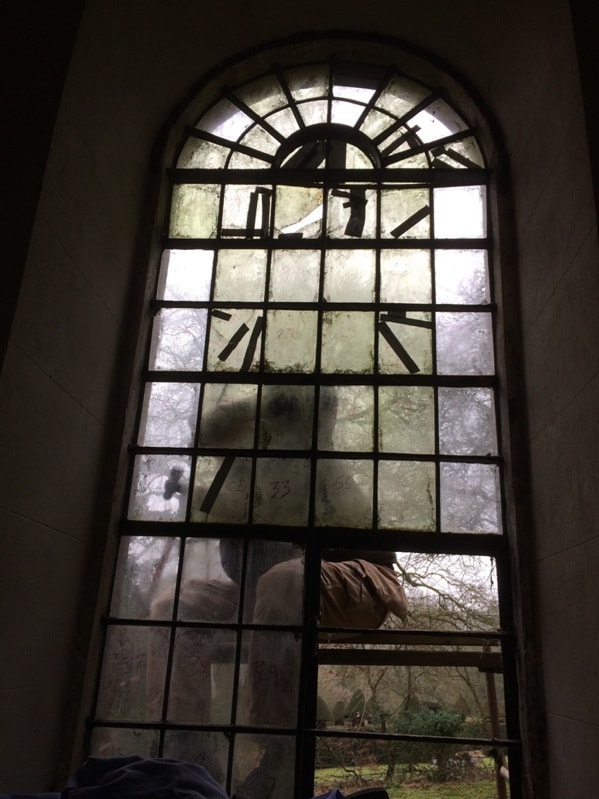

Only the east window in the chancel’s north wall retained a large proportion of the historic 18th-century glass. Even in this case, mild steel T-bars were installed to support the leaded glass panels. Over time, these T-bars became a problem. They corroded and expanded as they aged, fracturing the glass they were supposed to save. On top of this, the glazing had been pointed using a very hard, cement-based mortar.

Working together on restoration

To address this we planned a programme of repairs. First, Andrew Townsend Architects assessed the damage. Then Peter Hawkins was appointed to do the conservation work with the help of Bath Architectural Glass Ltd (BAGL). They removed the glazing and T-bars to their workshop, and re-leaded the existing glass. In some areas, the original glass quarries had been shortened to accommodate the T-bars, so extra wide leading was added to fill the space. Fractures in the glass were carefully repaired using copper strips. They retained as much of the original glass as possible: it was only replaced where pieces were missing or repairs were impractical. In these cases, the restorers either used tint-less ‘antique’ glass or small pieces of crown glass of a similar colour to the originals. The original ferramenta (supporting ironwork) was treated and decorated too.

Can breakages be beautiful?

The repairs are so delicate that they look like spider’s webs and we think they actually enhance the look of the window. It reminds us of the Japanese technique of kintsugi, where broken porcelain is repaired with a gold lacquer. The repair is not hidden but becomes a feature, adding to the overall beauty. It would be unjustifiable to go to this much effort with most broken windows. In this case, however, the age of the glass and the importance of this surviving window meant that we went the extra mile to save every last fragment.